This week’s readings

- John Krygier and Denis Wood, Ce n’est pas le monde

- Morton Gulak et al., Mental Mapping in the Richmond Region: The Use of the Physical Environment in Building Regional Cooperation

- Lewis Robinson, The varied “mental maps” our students have

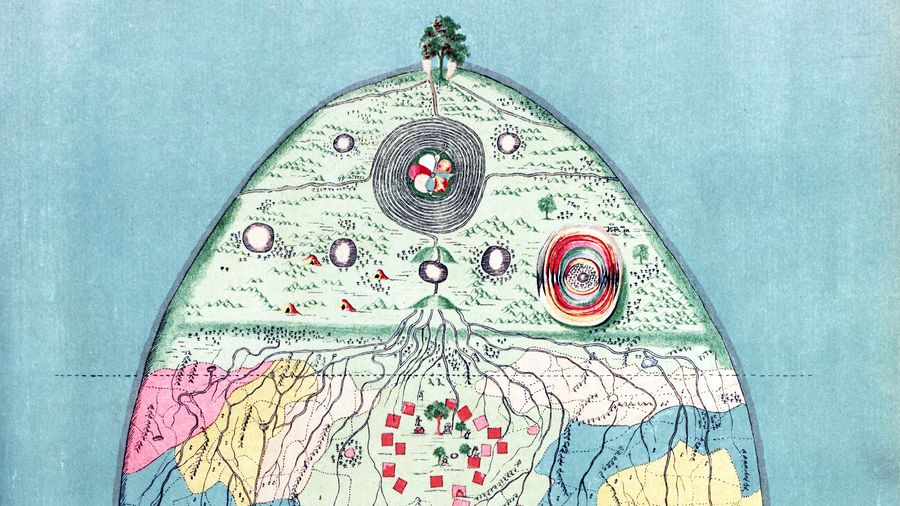

Krygier and Wood offer an interesting discussion on the nature of maps through a comic book chapter. They conclude that from representing reality, in all senses of the word, maps are propositions that make claims about reality, and can only ever capture aspects of that reality. By emphasizing certain aspects of space over others (i.e. counting the number of malls as an estimate of urban economic growth at the exclusion of other possible interpretations of city space – like the informal economy of slums), maps essentially create reality, and depend significantly upon the map-maker’s purpose or starting assumptions.

A comic book is an interesting, clever way of clearly and simply outlining key debates around what maps are – one that is itself a kind of representation.

Robinson expands on our understanding of representation in an article that delves into our “mental maps” of the world. Drawing on his experiences teaching geography courses at the University of British Columbia, Robinson tests his students’ preconceptions of what the world, within and beyond Canada’s borders, looks like. He discovers that map-making is an act of communication, one laden by our political assumptions of how the world ought to look like.

A chapter from Ellard’s book[1] deepens this analysis of mental maps, tracing our cognitive images of borders and nation-states to our imaginaries of everyday lived space – i.e., “the cartography of our own inner mental spaces”. He traces our contemporary cartographic perspectives to the human species’ – often clumsy – attempts to render geographic space legible.

In contrast to last week’s readings which sought to connect our (“modernist”, “abstract”, “reductionist”) mapping practices to historical transformations in modernity, Ellard sees our propensity to make maps as something innate to the species – for instance, drawing on Yi Fu-Tuan to argue that our upright posture has to do with our preference for straight, vertical and horizontal lines with which we construct our maps. This has at times made it difficult for us to accurately map out the world in all its oblique or muddled complexity.

Finally, in Gulak et al. urban planners were tasked to draw a map of the Richmond Region, Virginia in an attempt to test the “imageabilty” of roads, state boundaries, key historic sites, among other factors of apparent relevance to the individuals involved. Their work has implications for the use of mental mapping as a research methodology as well as an instrument for land use planning to improve conservation efforts, tourism, heritage site restoration, and regional economic cooperation.

[1] Colin Ellard, You are Here: Why We Can Find Our Way to the Moon But Get Lost in the Mall