This week’s readings:

- Christina Elizabeth Dando, “The Map Proves It”: Map Use by the American Woman Suffrage Movement

- Craig Dalton and Liz Mason-Deese, Counter(Mapping) Actions: Mapping as Militant Research

- Rhiannon Firth, Critical cartography as anarchist pedagogy? Ideas for praxis inspired by the 56a inforshop map archive

- Sebastian Cobarrubias and John Pickles, Spacing movements: The turn to cartographies and mapping practices in contemporary social movements

Cobarrubias and Pickles set the tone for this week’s papers. They note that a range of studies in the critical geography literature have moved beyond deconstructing maps toward surveying the spatialities of social movements, and the way social movements themselves think and engage spatially.

Cartography in the service of emancipatory politics is cartography that rearticulates spatial imaginaries in a way that contests ‘common sense’ notions of space and challenges contemporary power relations.

If conventional maps seek to render us objects visible to the control of state, corporate, or imperial power, then cartography of this kind allows us to become subjects mapping out the dynamics of such power by rendering it visible, and malleable, to collective political action. It allows us to lay a finger on the otherwise insidious and ‘invisible’ networks of power that permeate the globe and mask its real inequalities. It affords new ways of understanding our place in the world by exposing forms of enclosure, dispossession, division, and exclusion which challenge globalist arguments that suggest we are heading toward a more prosperous, integrated, and ‘flattened’ future.

They mention two examples of critical cartographic projects that have achieved just that. One was by the Bureau d’Etudes which focussed its efforts on the European Union (EU). It drew attention to the messiness of the EU project, whose cross-cutting flows of transnational capital, regulatory institutions, legal norms, think tanks, and activist networks belie notions that corporations and governments are the only relevant actors reproducing the EU as a contested space.

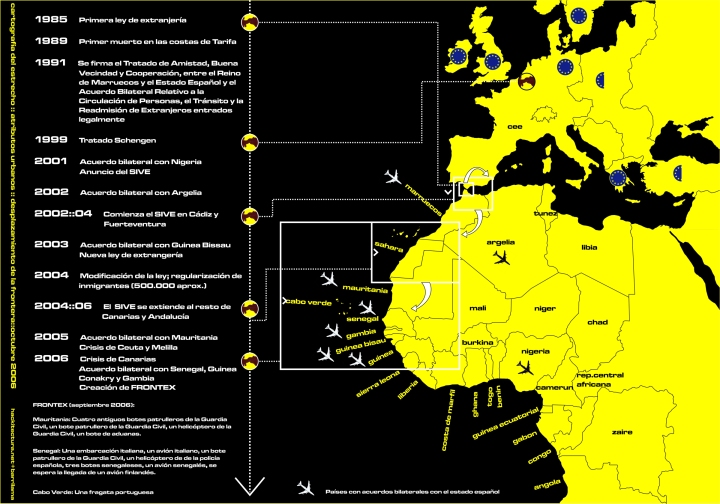

Hackitectura, on the other hand, consists of networks of refugees and their advocates, who have set for themselves the task of “deleting the borders of fortress Europe”. Hackitectivists contest the militarization of the Spanish-Moroccan border, chipping away at the racialised divides that set Europe apart from its African or Asian Other.

Using Hackitectura and other examples in the critical GIS literature as starting points, Dalton and Mason-Deese mention the experiences of the Counter Cartographies Collective (3Cs) at the University of Carolina-Chapel Hill in their discussion of “autonomous cartography”.

Autonomous cartography unhinges official narratives that territorialize borders as fixed and impermeable, reterritorializing in its place a vision for spatial justice which seeks answers to the question, as Doreen Massey once put it, of how we might live together. This is a cartography that spells the difference between mapping what is, and mapping what can otherwise be. It is in the very process of mapping other-possible-worlds that the tyranny of no alternatives can be transcended.

Dando’s article focuses on a more historical example in the American women’s suffrage movement.

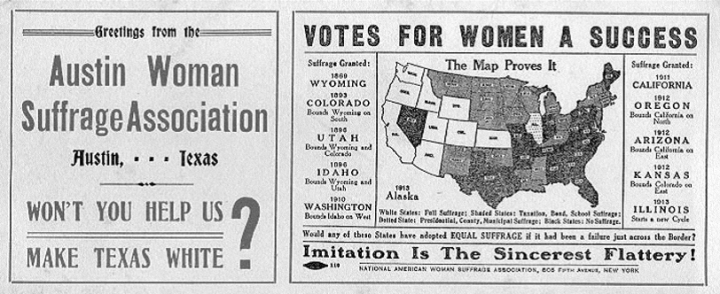

At a time when maps as communicative devices were increasingly entering into the public consciousness as a ‘legitimate’ media of truth, suffragists reappropriated their symbolic power – one that gestured toward truth and scientific authority in the eyes of the American public – in the struggle for women’s right to the vote.

While these efforts did result in the expansion of women’s rights and the inclusion of ‘gender’ as a distinctive right expressed in spatial terms, tensions within the suffrage movement hinged on its failure to surmount the white|black racial binary, and broader class divides that at times alienated the middle-class leadership of the women’s movement from working class voters.

This was clearly the case in a map produced by the Austin Woman Suffrage Association (AWSA) in 1913, which drew on white symbolism and at least implicitly fought for the right of white women to vote to ensure a higher proportion of white voters in the United States:

The suffragists were compelled, for pragmatic reasons or otherwise, to negotiate their rights on the terms of a racialised state, and in a language of colour that they felt would legitimate their claims.

The article concludes with the words of feminist activist Audre Lorde which challenge even attempts at ‘critical’ cartography: “for the master’s tools will never dismantle the master’s house. They may allow us to temporarily beat him at his own game, but they will never enable us to bring about genuine change”.

Indeed it is this which Firth emphasizes in her discussion of affinities between critical cartography and anarchist theory, which both proceed from the assumption that maps are not value-neutral devices. Instead cartographic ‘truth’ is created, as opposed to a ‘reality’ captured and measured through relative degrees of scientific accuracy. Distinguishing what is scientific from what is not is itself a function of power. But so is the compulsion to negotiate truth claims in the language of ‘oppressive’ power structures.

For instance, well-meaning counter-cartographic projects like those mobilised by advocates of indigenous peoples’ land rights tend still to negotiate their claims within the parameters acceptable to state institutions and corporations. While no doubt useful for the purposes of negotiating rights for the marginalised, even these tend to reinforce the legitimacy of existing institutions while diluting their own radical potential.

Moreover counter-hegemonic mapping typical of Marxist-inspired projects, or movements like the AWSA, rely on singular truth claims that silence other voices while hardening divisions between oppressor|oppressed. By using the instruments of the oppressor to gain legitimacy, these are simultaneously translated into hegemonic logics, instead of opening space/s for a dialogical encounter between both, and forwarding new forms of legitimacy for other ways of being in the world.

Anti-hegemony, by contrast, rejects the terms of power, attempting instead to shift the very parameters of debate, through different ways of engaging and transcending regimes of power in the “here-and-now”. It relies on alter-epistemologies that emphasize the role of affect and emotion as alternative cartographic logics.

Firth further argues that discussions of critical cartography in the academic literature tend to be theory-heavy without much interlude into how real social movements operationalize its assumptions in the realm of praxis. She takes as an example the 56a infoshop, an anarchist collective that started out as a food cooperative in South London. A 2005 map festival was what started the infoshop’s backroom map archives: a collection of alter-geopolitical maps, affective maps, collective walks and ‘radical history trails’ – juxtaposed to regular maps – that invoke visions for real utopias.